A behavioral approach: A must for today’s financial advisor

A behavioral approach: A must for today’s financial advisor

When advisors understand the unique motivators, biases, and constraints of each of their clients, they can put them in appropriate portfolios that help mitigate detrimental behavior. Advisors who apply behavioral finance principles in their practice can more readily build a unique element of trust and customization for each client relationship.

Assumptions in traditional finance include that markets are efficient and players are rational. But, as we have seen in each of the financial crises that have plagued the last 100 years, neither of these assumptions holds entirely.

Behavioral finance takes a more practical approach, identifying how people (and markets) actually behave, rather than how economic models prescribe they should behave. While topics in behavioral finance have been trending lately, the research goes back decades. It’s important for advisors to learn how to apply behavioral finance to their practice to help their clients make better decisions and lead to better financial outcomes.

When advisors understand the unique motivators, biases, and constraints of each of their clients, they can put them in appropriate portfolios that help mitigate detrimental behavior—like panicking when the market is going down (or up) and selling low (or buying high). Armed with a deeper understanding of their clients, advisors are better able to address any fears, biases, or special circumstances and communicate in a way that is more impactful, which can be the biggest benefit of having a financial advisor. In fact, a 2016 study by Vanguard shows that working with a human advisor who incorporates wealth-management best practices can potentially improve returns by 3%, with 50% of the increase attributed to behavioral coaching. In a low-rate environment, this is incredibly important. Compounded over time, it could mean the difference between retiring on schedule or not.

In an industry defined by trust, communication is the most important factor in client satisfaction–even more important than returns. And with new regulations around knowing the client, it’s more important than ever to dig deeper than standard deviation and expected return—deeper than age and time to retirement—and understand what really drives client behavior.

Two types of biases

All investors, professionals included, are prone to various biases. Although the word “bias” tends to have a negative connotation, it really just means humans act differently than economic models suggest they should, whether it’s due to past experience, inexperience, or emotional triggers creeping in. There are two categories of biases—emotional and cognitive—and investors tend toward one primary type. Emotional biases are driven by intuition or impulse. The classic struggle between fear and greed falls in this camp.

All investors, professionals included, are prone to various biases. Although the word “bias” tends to have a negative connotation, it really just means humans act differently than economic models suggest they should, whether it’s due to past experience, inexperience, or emotional triggers creeping in. There are two categories of biases—emotional and cognitive—and investors tend toward one primary type. Emotional biases are driven by intuition or impulse. The classic struggle between fear and greed falls in this camp.

Some investors have an emotional attachment to positions they hold. Perhaps the positions were bequeathed by a deceased parent or spouse and, even if the security is not appropriate for the investor’s own risk target, they continue to hold them due to endowment bias.

Regret aversion is another emotional bias whereby an investor is loath to miss out on the latest trend, so they may buy into a position that is outside their risk budget. Emotionally biased investors may also hold on to losing positions too long with the fear that the position will bounce back, triggering the painful feeling of regret. Regret aversion is a very strong bias, and even many advisors fall prey to its trap.

Cognitive biases explain other types of behavior resulting from errors in calculation, faulty reasoning, misremembering, or misunderstanding what happened in the past. Most professional investors harbor cognitive biases because, while they are trained to look out for emotional biases, they tend to have a blind spot for the cognitive mistakes they make. A classic example is the price at which an investor is willing to sell a stock. Many times, this price is related to the purchase price. For example, if an investor buys ABC stock for $100 per share, especially if the stock initially rises in price, the investor is unwilling to sell it when it drops below $100, even if the prospects for the company have diminished.

The investor becomes anchored to that $100 and thinks, “If I could just break even, I would sell,” which is obviously irrational. The company could be worth $40, and the investor would be better off selling it for anything above its calculated intrinsic value. After a stock is purchased, and aside from tax consideration, the $100 price is irrelevant and should not be considered when evaluating what the stock is worth. It’s important to consider what types of biases an investor holds, as it informs not only how an advisor should structure the client’s portfolio, but also how the advisor should frame discussions around gains and losses, risk and reward.

Beyond biases, a behavioral finance approach also considers how comfortable investors are with risk. Traditional risk surveys examine the investor’s ability (or “capacity”) to take risk, considering factors such as age, wealth, income, time to retirement, and any inheritance plans. This is not enough. It leaves out the human element of active decision-making. Not all investors of similar age, wealth, and income levels are comfortable taking the same amount of risk in their portfolios. This is a vital consideration because it informs the advisor on how a client will behave when faced with a market event, such as an equity drawdown, or a life event, such as the purchase of a house. Understanding how an investor will respond to volatility, drawdown, and uncertainty is important in making sure they stick with their investments in the long term.

Putting behavioral finance into action

Keeping track of the behavioral biases and risk preferences of each client can be challenging, and so can putting those insights into action. But there is a scalable and effective solution for both. The key to recalling client preferences at a glance and providing the most relevant, personalized experience possible to a sizable client base is segmentation and, more specifically, persona segmentation. Segmenting contacts by persona is an excellent approach for making behavioral biases actionable and keeping clients engaged with individualized communication. Finworx360 helps advisors identify the persona of each client through its Behavioral Risk Survey.

The online survey segments an advisor’s book of clients based on the dimensions of risk and biases, and then provides a communication framework for how to best relate to each client and approach key discussions. The survey is composed of questions about risk and follow-up questions designed to surface biases.

Here’s one sample question:

Which of the following statements most closely describes your attitude toward investing?

- Minimizing losses is most important.

- I am equally concerned with minimizing losses and maximizing gains.

- Maximizing gains is most important.

Questions like the one above are used to calculate the investor’s risk score. Based on their calculated risk score, the investor is directed to questions that identify biases associated with their specific risk tolerance. An example asks respondents to rate how much they agree with the following statement:

“The price I paid for an investment is a major factor when I consider selling an investment.”

The answer to this question indicates whether the investor shows signs of anchoring and adjustment bias.

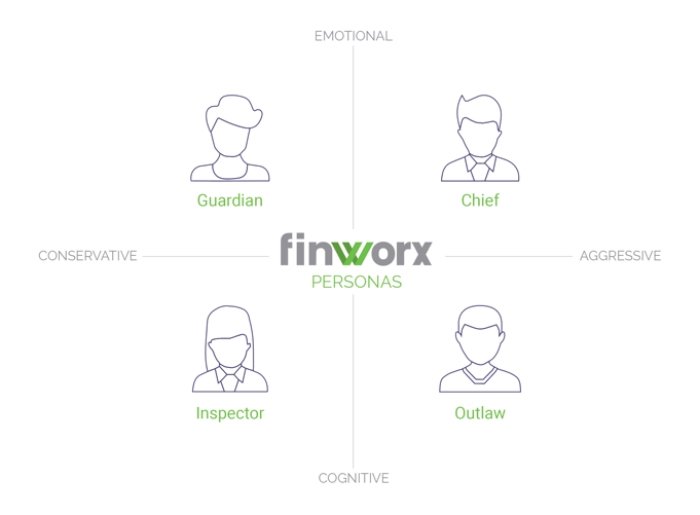

Based on a client’s answers to the Behavioral Risk Survey, they are segmented into one of four investor personas, each of which represents a unique combination of behavioral biases and risk preferences.

Source: Finworx

The names of the four personas—Guardian, Inspector, Outlaw, and Chief—give some indication of the type of investor each represents while allowing advisors discretion in the level of detail to discuss with their clients. For example, the Inspector is prone to follow leads and investment tips from friends or headlines, and typically does some independent research. Inspectors approach investing with a cognitive framework and tend toward biases such as availability and confirmation. The Guardian is the most risk-averse persona and holds emotional biases, such as endowment and loss aversion.

The Outlaw is very fluent in financial matters, tends to be contrarian, has a high risk tolerance, and mostly exhibits cognitive biases such as hindsight and mental accounting. The Chief is the most risk-tolerant persona and holds emotional biases such as overconfidence and self-attribution. Each persona responds differently to market events, taxes, advisory fees, and/or life events. Investor personas help advisors frame investment discussions as effectively as possible to deliver personalized communication at scale.

How should financial advisors proceed?

Concepts of behavioral science have been applied in many industries to increase the effectiveness of communication. With the various cognitive and emotional biases constantly at play in investing, combined with tightening industry regulations, financial services represents one of the most appropriate fields for leveraging a behavioral approach. Advisors who recognize the benefits of behavioral finance but have yet to fully apply it to their practice should look for a comprehensive solution that streamlines as many of the following steps as possible:

- Determining which behavioral factors most prominently impact clients’ decision-making processes.

- Measuring as accurately as possible each client’s willingness to take risk.

- Finding specific ways to communicate based on clients’ given risk preferences and behavioral biases.

- Segmenting the advisor’s book based on behavioral insights, risk attitudes, and communication methods.

Once these steps are incorporated into an advisor’s strategy, a unique element of trust and customization can be reached in each client relationship. What better way is there to improve outcomes for clients and advisors than by focusing on human behavior?

The opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of Proactive Advisor Magazine. These opinions are presented for educational purposes only.

Miranda Carr, CFA, is president of Finworx. She applies behavioral finance concepts across messaging and investment insights, manages market research, and collaborates on thought-leadership efforts. Ms. Carr has an MBA from Columbia Business School and is experienced in wealth management, portfolio management, and asset allocation. She has been portfolio manager for a global macro investment strategy, served on the investment committees for several alternative funds, and is an advisor to the University of Tennessee’s Torch Funds. For Ms. Carr’s take on behavioral biases, check out her “Thinking Like a Human” podcast series at finworx.com.

Miranda Carr, CFA, is president of Finworx. She applies behavioral finance concepts across messaging and investment insights, manages market research, and collaborates on thought-leadership efforts. Ms. Carr has an MBA from Columbia Business School and is experienced in wealth management, portfolio management, and asset allocation. She has been portfolio manager for a global macro investment strategy, served on the investment committees for several alternative funds, and is an advisor to the University of Tennessee’s Torch Funds. For Ms. Carr’s take on behavioral biases, check out her “Thinking Like a Human” podcast series at finworx.com.

Recent Posts: