Think investor sentiment is an insignificant indicator? Think again.

Think investor sentiment is an insignificant indicator? Think again.

Experts are combining social media, data science, and behavioral research to give new meaning to the concept of investor sentiment. Some of the results may surprise you.

If there were an award for the most intriguing financial market phenomenon that never quite lived up to its expectations, investor sentiment would be a contender. The relationship between the stock market and investor mood was postulated a century ago by Charles Dow, and it tends to be deceptively intuitive. But since that time, only limited progress has been made in even understanding the nature of that relationship, much less using it effectively for market analysis or forecasting.

Since there is little consideration of investor mood in the classic finance theories of the mid-1900s, such as EMH (efficient market hypothesis), MPT (modern portfolio theory), and CAPM (capital asset pricing model), there is limited use of sentiment in institutional money management. It is employed most often by options traders, who use put-call ratios and volatility as sentiment measures, and technical analysts, who use indicators such as price momentum, breadth, 52-week highs and lows, and relative strength as proxies for sentiment. Because they are mere proxies, however, the best these indicators can do is provide clues to sentiment that will always be muddied by extraneous activity that can render them at best ambiguous and at worst misleading. While not generally strong enough individually to offer a systematic approach, sentiment proxies are typically used to confirm or negate other signals.

At the same time, broad-based surveys of investors have been around for decades. Yet they have provided little, if any, useful information beyond the observation that investor mood appears to be a contrary indicator to price at major market peaks and troughs. This fact, however, usually just provides rear-view affirmation for major turns and does not add to our real-time ability to identify major tops or bottoms as they occur, much less predict them.

Surveying specific subgroups such as CFOs, purchasing agents, or corporate insiders offers a bit more appeal than retail investors, but these still suffer from the universal pitfalls of all “opinion” surveys: timeliness, high expense, and the lack of a concrete connection between people’s stated feelings of optimism or pessimism and their actual behavior.

Measuring sentiment by survey is thus inherently problematic. If you ask 100 people whether they are bullish or bearish, you will typically find a compilation of responses representing 100 different interpretations of what bullish or bearish means, what time frames people are using, what exactly they are bullish or bearish on, and to what degree they are one or the other.

In his book “Fooled by Randomness,” Nassim Nicholas Taleb quipped that he “could never understand the concept of ‘bullish’ or ‘bearish’ outside their purely zoological consideration.” His comment underscores the fact that bullish or bearish predispositions have no universal meaning, do not express any notion of timing or degree, and do not directly translate into purchase or sale intentions under any circumstances.

For that matter, experts can’t even agree on whether sentiment precedes market price action or reacts to it. Most people tend to view their mood as the result of market action, not its cause. If the market rises, we are happy—if it falls, we are sad. But Nobel laureate Robert Shiller points out in “Irrational Exuberance” that such thinking falsely views the markets as being influenced by acts of God or other external events rather than recognizing it as the result of how we as participants react to those events.

Author Robert Prechter espouses an opposing theory that mood changes precede market action—that the market rises or falls as a consequence of the changing mood of the participants. Most academics appear to accept an interpretation that incorporates both Prechter’s and Shiller’s viewpoints into a scenario where there is a continuous feedback loop between mood and market price action. That view holds that mood can both precede and result from market movements, leaving us with a circular system that makes sentiment a hopelessly complex variable for anyone to use effectively.

Academia has pondered the subject of sentiment at great length, especially since behavioral science entered into the mix. Numerous papers have addressed specific price anomalies that have been linked to behavioral biases, but academics have not generally found broad sentiment measures to provide valuable insights. Using more than 20 years of data, Santa Clara University professors Michael Solt and Meir Statman examined the effectiveness of the so-called “Sentiment Index,” a popular index during the 1960s to 1980s. The index was derived from a survey of investment advisors and thought to be a contrary indicator. In September 1988, Solt and Statman wrote in the Financial Analysts Journal that “the [sentiment] index is useless as an indicator of forthcoming stock price changes. The number of correct forecasts by the index is equaled by the number of incorrect forecasts.”

Like so many other things, though, the internet and social media are changing the very nature and use of sentiment. Corporate America has fully embraced social media as a godsend for tapping into consumer views on products and brands. Amid some fits and starts, the investment community may be waking up to its potential now as well.

Like so many other things, though, the internet and social media are changing the very nature and use of sentiment. Corporate America has fully embraced social media as a godsend for tapping into consumer views on products and brands. Amid some fits and starts, the investment community may be waking up to its potential now as well.

Social media provides a mountainous flow of information from individuals in the form of tweets, blogs, message boards, online chats, and forum posts (collectively dubbed “user-generated data”). This data theoretically contains valuable nuggets of information on people’s emotional reactions, perceptions, and even purchase or investment intentions. Initial work with such data showed that the sheer volume of these reactions alone provided clues that could be valuable in explaining some aspects of market price behavior, but that was too crude to be useful. Since then, the field has made considerably more progress.

Three developments have coincided to create the “perfect storm” that is powering a huge makeover in the use of public sentiment in investing. The first, of course, is social media, the ubiquitous form of information exchange that not only facilitates information flow to hundreds of millions of people in real time, but also provides instant feedback mechanisms that allow them to express their feelings and reactions. This completely overturns the survey paradigm by delivering fresh, unsolicited user commentary from magnitudes more people than surveys could ever reach and does so in less time than it would have previously taken to design the first question on a survey. Social media data on securities price movements can now be seen in real time, moving the concept of surveying an audience from the Stone Age to the digital age overnight.

While massive and lightning fast, however, social media data is unstructured and a lot “noisier” than survey data. So, in the same way that miners cull through a ton of rock to get 1/20 of an ounce of gold, data miners sift through tons of extraneous social data for sentiment gold.

That’s where the second development comes in. Data science, which broadly encompasses data mining, artificial intelligence, machine learning, and natural language processing, has become an absolute requirement for using social media data. Together, social media and data science now provide vast new amounts of raw information and a sophisticated filtering system that can distill it into useful nuggets.

That said, social media and data science are both still young, and there has been a substantial learning curve involved in developing mainstream applications for investment purposes. Integral to that learning curve is the third development in the mix: behavioral science. Gold mining operations have a number of tests and processes they perform on raw ore to determine whether they, in fact, have gold and how much.

In the social media world, there are no hard science tests that can be performed on data to evaluate its effectiveness. Instead, we must rely on behavioral filters that interpret the data nuggets uncovered in light of what we know about human biases and behavior. Without a behavioral overlay, the early days of using social media data were fraught with missteps and false assumptions.

Today, there is a robust industry for collecting, filtering, analyzing, and interpreting social media data for consumer-facing companies, but challenges remain in using this data for financial market analysis. One of these is the industry’s mindset, which is heavily influenced by a regulatory environment that took a very skeptical view of social media for some time.

Another is that behavioral finance is full of nuances that are not yet fully understood. In marketing applications, social media data tends to be more straightforward. Comments about products or services can be directly mapped to product features, price, brand perceptions, and ultimately to a propensity to purchase. In addition, marketers were doing this for decades before social media arrived, and they have all that experience to draw from.

Behavior in finance and investing is far less intuitive and more complicated. Instead of a scenario that has only a purchase option, investors essentially have three potential actions (buy, sell, or hold) plus the potential for successive actions over time. Moreover, in investing, simple supply and demand considerations don’t necessarily apply. If an attractive stock gets cheaper, people might initially buy more, but at some point in a steep decline that behavior abruptly reverses and that results in selling. Thus, for financial behavior, you not only need the data, but you also need expertise in behavioral finance to know how to interpret it.

Assume, for example, that sentiment on the exchange rate between the U.S. dollar and the Chinese yuan appears to be turning negative as a result of the coronavirus outbreak. Does that by itself suggest that the yuan is about to start a new downtrend against the dollar? In many situations, sentiment turns do precede trend changes, but not all. Sometimes, it takes multiple events or simply additional time for sentiment to turn into actionable behavior. Sometimes, a price trend will unfold first, and a change in sentiment will follow. Social media and data science can reveal the sentiment change, but an understanding of how that translates into expected behavior is critical to using that data to facilitate investment decisions. That’s a work in progress.

The combined effect of user-generated data and a scientific process to distill it into usable information has spawned new terms such as “emotional data intelligence,” which is one of the new ways to describe sentiment. Another is “social sentiment,” which is being used to create “social sentiment indicators,” which in turn can be used to rank stocks by their “S-scores.” The resulting scores are now being used to create new sentiment indexes.

The new world of social sentiment is completely unlike its prior incarnation. It is now a continuously evolving science in which humans rely on artificial intelligence to extract potentially meaningful conclusions from huge and disparate piles of social media data, often in real time. These conclusions can then be served up in a wide variety of statistical or visual formats that are largely left to the users to interpret. There is no universal approach to either the data sources used, the algorithms or filtering logic employed, or the method of displaying the results, so social sentiment data can be as varied as the entities analyzing it.

One individual at the heart of this process is Dr. Richard Peterson, a psychiatrist and the CEO of MarketPsych. Dr. Peterson is also the author of several books, including “Inside the Investor’s Brain,” “MarketPsych,” and most recently “Trading on Sentiment,” in which he describes his experience running a market-beating social-media-based hedge fund and creating the Thomson Reuters MarketPsych Indices.

Peterson admits that the learning curve on using social sentiment has been considerable and that the industry has come a long way even since he published his book on sentiment in 2016. He currently sees two clear use cases for social sentiment data:

- Positive “sentiment momentum” about fundamentals (for certain types of stocks) is shown to lead prices higher over days to even years.

- “Sentiment reversals” are shown to lead prices at extremes (especially down, and again for certain types of stocks and commodities).

He notes, however, that “sentiment momentum is only valid if emotions are low because high positive/negative emotionality is typically a sign of overreaction and mean reversion is more likely to follow in this case.” Peterson also points out that people today are zeroing in on specific aspects of sentiment on specific instruments or price relationships such as earnings sentiment or event-based sentiment on the effects of things such as currencies.

For the record, MarketPsych is just one of many new companies in this space. Others include Dataminr, Refinitiv, Social Media Analytics, Stocktwits, StockPulse, and iSentium.

The idea of using social sentiment has evolved much since its inception. Some early pioneers saw social media data as having the potential to surface information on companies that had not yet been made public or been fully reflected in price. While a “scoop” of this nature might occasionally be uncovered, there was no way of knowing which of the thousands of such situations were real or meaningful, thus rendering this approach moot. It is said that perhaps only 10% of the data analyzed produces meaningful information. In addition, data can be accurate without necessarily being predictive. It’s rarely going to be as simple as “if the data says this, do that.”

The industry clearly has a lot of additional work to do in determining what types of social indicators are meaningful, what sources are more trustworthy, and how this data can be systematically used to enhance portfolio construction, monitoring, and management. Nonetheless, according to emotional data intelligence company StockPulse, social sentiment has already found a reception among hedge funds, asset managers, banks, exchanges, private equity companies, financial publishers, online brokers, news portals, and research companies. And there is growing evidence that the area may hold significant promise:

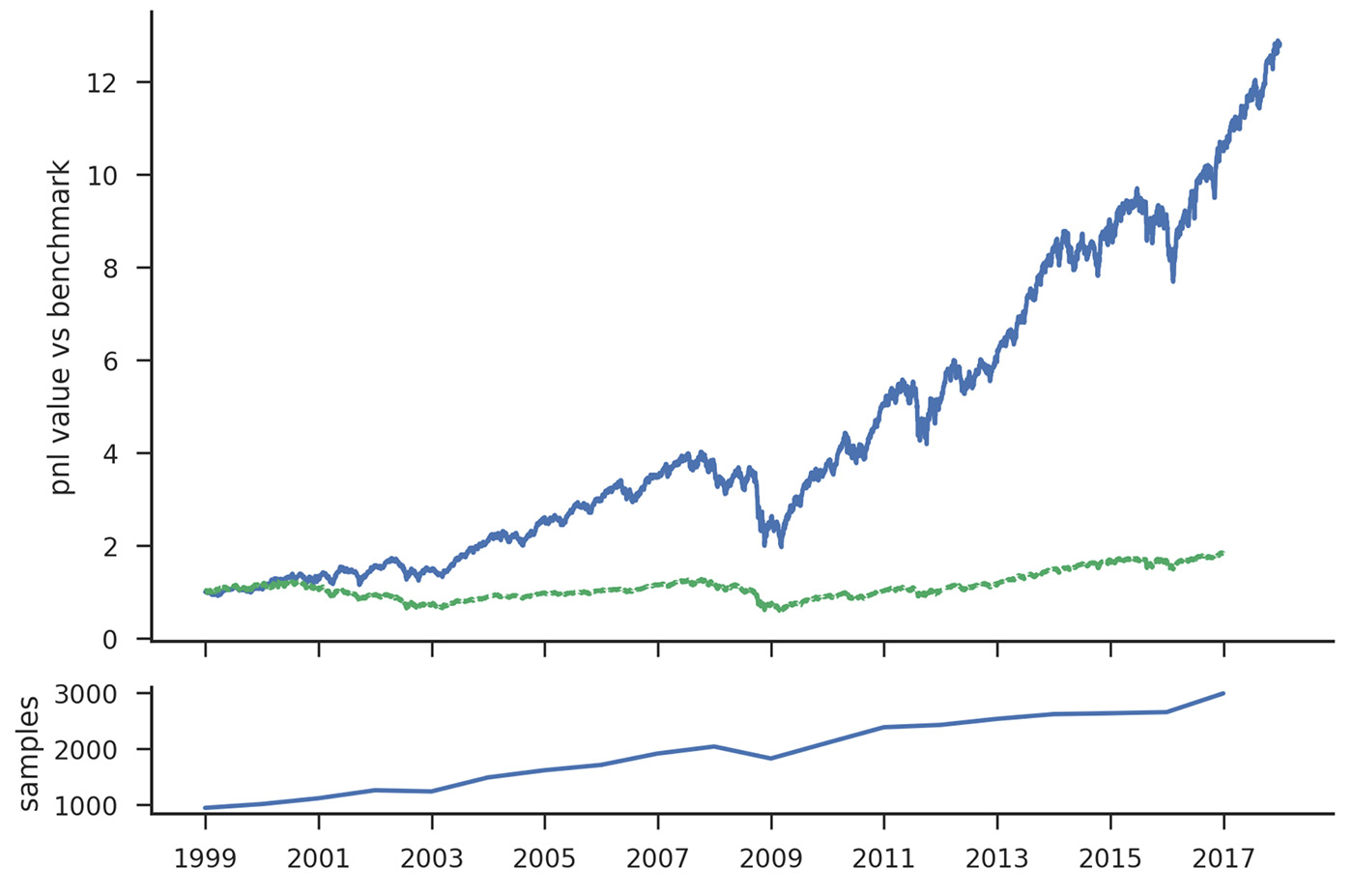

- MarketPsych created the following chart to illustrate the strength of positive sentiment momentum. The chart shows the cumulative performance of a hypothetical portfolio of 200 stocks determined to have the highest positive sentiment readings from the top 1,000 stocks measured in media “buzz” (volume). (One-twelfth of the portfolio is rebalanced each month and no transaction costs are included.) The portfolio is shown in blue versus the S&P 500 in green.

Source: MarketPsych

- In 2010, a study by the Universities of Manchester and Indiana suggested that the social sentiment data could actually help to explain stock market movements. Johan Bollen, a business professor at Indiana University, reported that Twitter data could predict the Dow Jones Industrial Average with 87.6% accuracy.

- A study from financial data services provider Markit, covering December 2011 to November 2013, showed that stocks with positive social media sentiment generated cumulative returns of 76% compared to -14% from negative-sentiment stocks.

- The Chicago Board Options Exchange (CBOE) created an index using S-scores from Social Market Analytics. The SMLCW Index tracks an equal-weighted portfolio of 25 stocks drawn from the CBOE large-cap universe based on 5-period S-scores. Quick math on the performance of this index between its inception in September 2014 and February 2020 (65 months) shows a total period performance of 94.1% versus 67.7% for the S&P 500.

The reality is that managers are continuously assessing news, fundamentals, and price action to evaluate how they think the market is pricing a particular stock or commodity. The market “is people,” and while market participants are stating their views through buying and selling, those same people are expressing themselves frequently through social media. The information gleaned from social media should, therefore, provide valuable context, depth, and color to market sentiment. We just have to refine our process of extracting it.

Richard Lehman is the founder/CEO of Alt Investing 2.0 and an adjunct finance professor at both UC Berkeley Extension and UCLA Extension. He specializes in behavioral finance and alternative investments, and has authored three books. He has more than 30 years of experience in financial services, working for major Wall Street firms, banks, and financial-data companies.

Richard Lehman is the founder/CEO of Alt Investing 2.0 and an adjunct finance professor at both UC Berkeley Extension and UCLA Extension. He specializes in behavioral finance and alternative investments, and has authored three books. He has more than 30 years of experience in financial services, working for major Wall Street firms, banks, and financial-data companies.