In many ways, we are staring down the barrel of a loaded credit gun. Credit is often the “coal miner’s canary” to market downturns.

While a market implosion is unlikely, a marked deterioration of credit, specifically leveraged loans and high-yield bonds, could act as a huge ball and chain on equity markets. An understanding of leveraged buyouts (LBOs) and the debt that fuels them is essential for all investors who care about market risk.

LBOs: What are they and how do they work?

When Toys R Us filed for bankruptcy protection, the public bemoaned the evil private equity firms that led the beloved toy purveyor to ruin, but what actually happened?

An LBO is a transaction in which a company is purchased, usually by a private equity firm (a financial sponsor), to be taken private. The deals are typically financed by large amounts of debt. It is not unheard of to see sponsors using their own capital to cover only 20%–50% of the acquisition price, with leveraged debt covering the remainder.

The idea behind an LBO goes something like this: Let’s say a house is purchased as an investment for $100,000 with $100,000 cash. The house is subsequently rented out for $500 per month and sold five years later for $110,000. This transaction would yield a 40% return over five years ($10,000 in capital appreciation plus $30,000 in rent, divided by the $100,000 equity investment).

As an LBO, the house might instead be purchased with $50,000 of cash and a $50,000 bank loan. The $500 per month in rent collected is now used to pay down the loan balance during the life of the investment. For this example, we will assume a 5% interest rate and that the house is sold in five years.

Using leverage yields a 55% return versus 40% without leverage, when loan repayments and the same final sales price are considered. While this example is simple and conservative in its loan-to-equity assumption, it helps illustrate why private equity firms seek to use as much debt as possible when acquiring a company—leverage has the power to significantly increase returns. At its core, this is the idea behind a leveraged buyout.

What do private equity firms look for?

When examining targets, there are certain characteristics private equity firms look for: steady cash flows, limited business risk, limited need for ongoing investment, strong management, opportunities for cost reductions, lots of assets (to use as debt collateral), and a viable exit strategy (a way to sell the company).

While there are other criteria, these are the nuts and bolts. From a financial perspective, two main metrics are key for evaluating investments: cash-on-cash returns and the internal rate of return (IRR). Cash-on-cash is a back-of-the-envelope way to evaluate deals (all cash earned during the life of the investment, minus debt service and debt repayment, is divided by the initial equity investment—purchase price minus debt). The internal rate of return is a more detailed metric; without getting into the weeds, this calculation is affected by the cost of debt and the amount of time the investment is held. One way to improve IRR is to sell a target faster; the shorter the holding period, the higher the IRR.

With this last principle of IRR in mind, private equity firms typically seek to dispose of their investments within three to seven years. Two ways in which a sponsor can exit an investment are to sell the company in an M&A deal or to take the company public.

When these traditional means of exiting an investment can’t be used (due to lack of buyers, poor market conditions, etc.), sponsors can perform a “dividend recapitalization” to boost returns. Once a significant portion of debt has been paid down, the private equity firm goes back to a lender and again maxes out the amount of debt they can borrow. This money is then used to pay the equity holders (primarily the private equity firm) a large dividend. The cycle of using the company’s cash flow to pay down debt starts all over again. This is akin to taking out a home equity line of credit to pay yourself.

What this means in today’s interest-rate environment

The effect of 10 years of cheap money (low rates) sloshing around the system has been a massive expansion of leverage. As rates decrease, large loans can be serviced for the same periodic payment that once supported smaller loans. This encourages inflated valuations as sponsors and strategic acquirers can afford to pay more for companies. The result has been a plethora of leveraged buyouts—some of which have been the largest ever seen—and a flood of high-yield bonds and loans. Some have gone as far as to call the current environment a private equity bubble.

Wall Street tends to have a short memory. Credit bubbles follow a typical pattern: lending requirements become looser, valuation practices become less stringent, and non-bank lenders (shadow banks) emerge. Over the past several years, we have seen each of these criteria checked off.

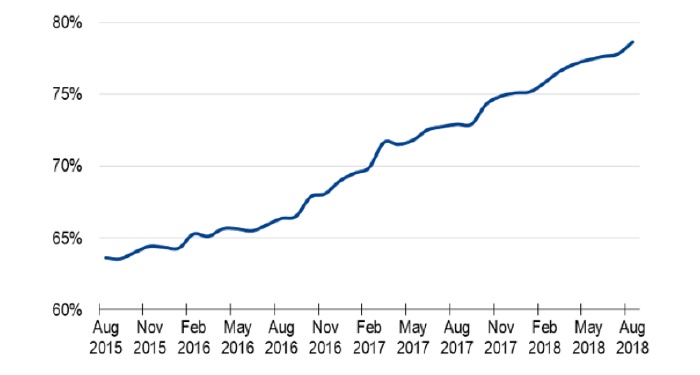

Since 2015, we have seen a huge uptick in the number of “covenant-lite” leveraged loans. Historically, leveraged loans have featured maintenance covenants, lender guidelines that require borrowers to maintain certain metrics, undergoing annual tests to make sure set levels have not been breached. Covenant-lite loans, by contrast, feature “incurrence” covenants. These are far less restrictive and, instead of requiring the borrower to maintain certain metrics showing financial health, only require the borrower to be in compliance when taking certain actions (acquiring a company, paying a dividend, issuing more debt, etc.).

Leveraged Commentary & Data (LCD) wrote in September,

“The share of covenant-lite deals in the U.S. leveraged loan market continues to reach new heights. … As of August, cov-lite accounted for 78.64% of outstanding loans, up from 77.8% in July, according to the S&P/LSTA Loan Index. This is the 10th straight record.”

FIGURE 1: COVENANT-LITE SHARE OF U.S. LEVERAGED LOAN MARKET

Source: LCD, an offering of S&P Global Market Intelligence

Looking out to the next bubble?

We have entered a Federal Reserve rate-hike cycle. The secular bull market for bonds is over, and rates are rising. While highly levered healthy companies can survive increases in debt service costs, firms with questionable balance sheets, or firms bought at inflated valuations, may stumble and fall.

Fed rate-hike cycles tend to precede market tops and recessions. In this way, less stable levered firms face a double whammy. On the cost side, higher rates increase interest expense and, when a firm is at maximum leverage, such increases can be disastrous. On the revenue side, the economic contraction that often follows a rate-hike cycle squeezes the bottom line as the business generates fewer total dollars.

We have seen this story play out repeatedly before. Are we fully in a credit bubble? Is the market on the verge of an implosion? The answers are no and no. However, the volatility that can accompany the blowup of less stable companies or firms, levered to the maximum, is a significant risk factor for markets that all investors should recognize.

The opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of Proactive Advisor Magazine. These opinions are presented for educational purposes only.

Jeanette Schwarz Young, CFP, CMT, CFTe, is the author of the Option Queen Letter, a weekly newsletter issued and published every Sunday, and "The Options Doctor," published by John Wiley & Son in 2007. She was the first director of the CMT program for the CMT Association (formerly Market Technicians Association) and is currently a board member and the vice president of the Americas for the International Federation of Technical Analysts (IFTA). www.optnqueen.com

Jeanette Schwarz Young, CFP, CMT, CFTe, is the author of the Option Queen Letter, a weekly newsletter issued and published every Sunday, and "The Options Doctor," published by John Wiley & Son in 2007. She was the first director of the CMT program for the CMT Association (formerly Market Technicians Association) and is currently a board member and the vice president of the Americas for the International Federation of Technical Analysts (IFTA). www.optnqueen.com

Recent Posts: