Is it possible to just say no to volatility?

Equity investments as an asset class have historically produced the greatest returns over time, but the process is often stressful for investors and their financial advisors. Could a simple tactic allow investors to “just say no” to volatility?

Stock market volatility has been back in the news with the first three quarters of 2015 reporting over 50 days with 1%+ days—days when the market moved more than 1% up or down. That compares to 38 days of 1%+ moves per year in 2014 and 2013, and, according to Ed Easterling of Crestmont Research, may be the leading edge of a new onset of volatility in the financial markets.

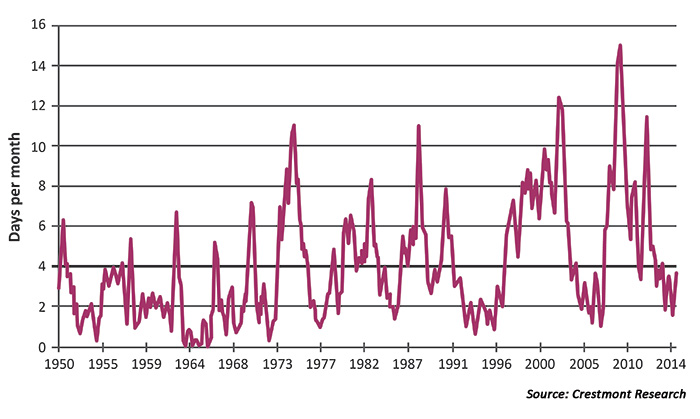

Back in January 2015, Crestmont Research published an informative chart (Exhibit 1) showing the market’s tendency over time to cycle between low- and high-volatility periods. When volatility falls below the historical average of four 1% moves in a month, high volatility tends to follow. “If history is again a guide, a surge to high volatility may not be far away,” Easterling opined, and the next nine months of 2015 were right on target with his expectations.

EXHIBIT 1: NUMBER OF DAYS PER MONTH WITH 1%+ S&P 500 CHANGES

Six-month moving average 1951–2014

High-volatility periods are times of greater risk and uncertainty in the market. These are times when investors are more prone to emotional decisions, when hair-trigger computer programs can launch market moves, and when negative news tends to carry more clout than the positive. Studies have shown that periods of high market volatility also tend to be times of lower returns. Which brings up the question, what if investors were to “just say no” to volatility?

The first problem is to identify periods of volatility clustering. Easterling provides a relatively simple approach to viewing volatility, using a six-month moving average to reduce market noise and smooth the trend. In his analysis of the S&P 500 back to 1950, he identified an average of four 1%+ days per month. Suppose investors were to use the same methodology to monitor market volatility, moving out of equities when volatility based on the six-month moving average exceeds 100% of the average, i.e., eight or more 1%+ days in a month?

Financial markets are neither random nor efficient, but move in patterns that create opportunities to manage risk and enhance returns over full market cycles.

At first glance, the idea is intriguing. Historically, volatility increases during market declines, peaking as the market reaches its lows. Given that volatility does indeed cycle, with periods of high volatility followed by periods of low volatility, it should be possible with the use of the lagging six-month moving-average indicator to reduce portfolio volatility—but at what cost?

The only catch is an argument that is often made to discourage market timing: What if one misses the best days of the market, with their ability to turbocharge returns? These days are by definition among the most volatile. This brings up the biggest drawback to using volatility as solely a measure of market risk. Volatility in and of itself is not necessarily a negative. Few investors object to having their portfolios increase by 4%, 5%, and even 10% in a single day. The problem is “negative” volatility, days when the 1%+ move is down.

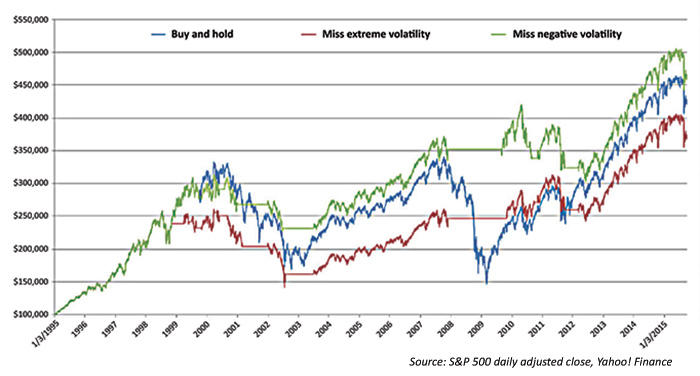

With that thought, backtests were run using the period from January 1995 through September 2015. The first test moved a portfolio invested in the S&P 500 index to the protection of cash whenever the six-month moving average number of days per month with gains or losses in excess of 1% was eight or more. The second moved the portfolio to cash only when the six-month moving average number of days per month with losses in excess of 1% was four or more. The results are shown in Exhibit 2.

EXHIBIT 2: GROWTH OF $100,000 INVESTED IN THE S&P 500

Over the 20-year period of this analysis, the “no first caps” strategy triggered trades ten times, and the “no first caps” strategy traded eight times. For each strategy, the shortest period out of the market was a month. The 2007-09 period saw the longest stretches of going to cash for each strategy—close to two years.

At the end of September 2015, a buy-and-hold investment of $100,000 in the S&P 500 was valued at $420,524; avoiding extreme volatility reduced the ending value to $367,753; avoiding periods of high negative volatility resulted in the best performance and an ending value of $457,877.

Avoiding extreme volatility clearly hurt returns. The model that avoided excessive volatility without discriminating as to whether the volatility was up or down tended to re-enter markets later and in some instances, move out of markets when the volatility was largely positive. When investors “say no” to all excessive volatility, they they may miss the good along with the bad. This comes back to the fallacy of basing risk on volatility alone. What matters is not volatility, but “negative” volatility. When the investor discriminates between high volatility and high negative volatility, performance improves.

Can investors “just say no” to all extreme volatility? Not without sacrificing performance. But this exercise does strongly suggest that “saying no” to negative volatility has the potential to produce better returns with less risk, and a smoother ride for the investor. It illustrates, in simple fashion, one of the core underlying principles behind many actively managed strategies that seek to avoid large episodic drawdowns: Financial markets truly are neither random nor efficient, but rather move in patterns that persist for sufficient time periods to be detected and acted upon, creating opportunities to manage risk and enhance returns over full market cycles.

Linda Ferentchak is the president of Financial Communications Associates. Ms. Ferentchak has worked in financial industry communications since 1979 and has an extensive background in investment and money-management philosophies and strategies. She is a member of the Business Marketing Association and holds the APR accreditation from the Public Relations Society of America. Her work has received numerous awards, including the American Marketing Association’s Gold Peak award. activemanagersresource.com

Linda Ferentchak is the president of Financial Communications Associates. Ms. Ferentchak has worked in financial industry communications since 1979 and has an extensive background in investment and money-management philosophies and strategies. She is a member of the Business Marketing Association and holds the APR accreditation from the Public Relations Society of America. Her work has received numerous awards, including the American Marketing Association’s Gold Peak award. activemanagersresource.com