When ‘passive’ investing isn’t passive: Active aspects of the S&P 500

Index investing is not necessarily buy-and-hold investing. Components and weightings of the S&P 500 are constantly in motion in response to market and business cycles.

The rise of index investing is typically based on the belief that no one is able to predict the market or the performance of individual investments accurately enough for active investing to outperform the market over the long run. Thus, the “very best” the investor can ever do is match the performance of the market. To achieve this, one invests in an index, buying and holding the “market.”

The simplicity of this approach is seductive. There’s no need to worry about risk or asset allocation, market cycles or investment styles. Everything is determined by the “unbeatable” market.

Why not jump on the index investing bandwagon and let the market take care of your clients?

For starters, index investing is investing without brakes. There are no controls to limit risk, to preserve capital in down markets, to assure that your client will have money to retire, or to meet other goals. In fact, index investing runs counter to the following investing wisdom, which has been gathered over decades of portfolio management:

- Don’t chase hot stocks.

- Diversify your portfolio across noncorrelated asset classes, industries, and market segments to balance risk.

- Rebalance periodically to maintain your desired allocation and limit the risk of one stock or sector adversely impacting the portfolio.

Ironically, while index investing has become the new “buy and hold,” as an investment, the S&P 500 Index violates the predominant beliefs of a buy-and-hold strategy. It is, at its most basic level, an active investment strategy with a strong momentum influence.

The S&P 500 is the most traded index of all, but it is also highly concentrated—85% of the assets in S&P 500 Index funds are managed by just five funds or ETFs: Vanguard 500 Index Admiral, Vanguard Institutional Index I, SPDR S&P 500 ETF, Fidelity Spartan 500 Index, and iShares Core S&P 500.

In addition to this somewhat mind-boggling fact, there are several other aspects of the S&P 500 as a trading vehicle that advisors and investors should understand:

1. The index is designed to reflect the performance of specific sectors of the market, based on the largest, most financially viable public companies:

- Sector allocations are set by a committee to reflect the impact of the sectors on the market—not the economy, not GNP, but the market.

- To be included, a company must have $5.3 billion in market cap based on publicly traded shares, with at least 50% of its shares available in the public market.

- Positive earnings under generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP) over the preceding four quarters, as well as the most recent quarter, are required.

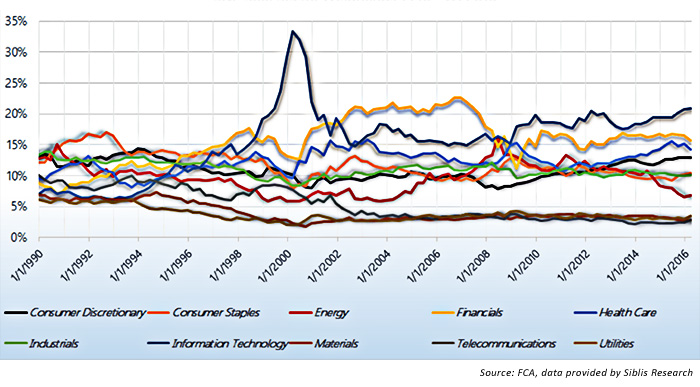

S&P 500: SECTOR WEIGHTINGS (1990–2016Q1)

Sector weightings have varied relatively dramatically over time. Information technology—i.e., the computer and software industries—has ranged from 6% of the index in the early 1990s to a high of 33% at the start of 2000 and is currently 20% of the index.

2. There is less-than-ideal diversification across noncorrelated asset classes.

- The S&P 500 is designed to be representative of the large-cap universe, not a necessarily desirable portfolio allocation. What matters is market capitalization for company inclusion, that is, the number of publicly traded shares times the market value of those shares.

- Nearly 40% of the S&P 500 is currently represented by two sectors: information technology and financials.

- Correlation between the S&P 500 and its sectors since 2007 has been in the 0.8 range with the exception of Telecom, which has hovered around 0.5. (Data from Bespoke Investment Group; perfect correlation is 1.0.) The S&P 500 and all but one of its sectors, therefore, move almost in lockstep. There is inadequate diversification across investment sectors that might counterbalance each other in a market downturn.

3. The S&P 500 “buys high” and sells when companies lose value, following a momentum-style investment approach.

- Inclusion in the S&P 500 increases demand to the extent that the average S&P 500 stock experiences a 4% jump in value when it is added to the index (according to analysis in a 2012 research paper published by the Federal Reserve Bank of New York). To be considered, the stock has to have exhibited increasing influence on its sector and the market and increased market value—that is, it needs to be a big, “hot” stock within its sector.

- Investments that are gaining market value are rewarded with a larger slice of the investment pie. With a decline in share value, the stock’s share of the index is reduced.

4. There is no real “buy and hold” to the S&P 500.

- In 2015, 24 companies were replaced in the S&P 500. Over the last 51 years, 20 to 30 component changes were made each year. Mergers and acquisitions, bankruptcies, deteriorating financial performance, and slumping stock prices can all be reasons for exclusion from the index.

- “Survivorship bias” allows the S&P 500 to escape the poor returns of some former index members.

- Allocations also change within the index to reflect changing market cap and sector weightings.

So what exactly is an investment in the S&P 500?

It’s a highly concentrated, minimally diversified investment in the largest, publicly traded, U.S.–headquartered companies. It’s monitored for performance with the relative losers booted out on a regular basis. Despite the 500 in the index’s name, the top 50 companies in the index have the greatest influence on its performance, representing approximately 50% of the index’s value. In 2015, it was estimated that for every $1 change in Apple stock, the S&P 500 rose or fell 0.6526 points.

And, it is undeniably active, beginning with the sector allocation and the inclusion requirements, to the index’s focus on market capitalization. What the S&P 500 doesn’t provide is active risk management. And, it doesn’t necessarily provide great performance. While stock price speculation may drive increases in share price, the companies’ size limits their ability to grow sales and income in the double digits. Doubling in size is far easier when you start with from a low base level. The bigger the company, the more elusive is explosive growth. Were it not for dividends, a buy-and-hold investment in the S&P 500 would have seen considerable volatility but virtually no gains from 2000 to 2011.

This isn’t to say that the S&P 500 isn’t a great trading vehicle. Although a buy-and-hold investment would have had minuscule gains from 2000 to 2011, there were opportunities to make considerable gains by being on the right side of the trend. In fact, among the S&P 500’s advantages for the active manager is its “active nature.” Inclusion in the index requires that the companies be financially sound and relative leaders in their market sector. Said the previously cited paper by the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, reinforcing the “momentum factors” of the S&P 500:

“We find that the firms included in the S&P 500 index are characterized by large increases in earnings, appreciation in market value, and positive price momentum in the period preceding their index inclusion. … On average, the increase in market capitalization in the two years preceding inclusion, adjusted for changes in the aggregate market level, is 56%.”

Further, the index methodology of the S&P 500 should weed out financial underperformers and assure that member companies hold significant market share. As S&P 500 Index investing grows, demand can push higher valuations for the S&P 500 companies, driving value. The sheer size of the S&P 500 funds also assures liquidity. Active management has the opportunity take the best of the S&P 500 and make it even better, adding risk management and the opportunity to leverage compounded returns by limiting losses.

Linda Ferentchak is the president of Financial Communications Associates. Ms. Ferentchak has worked in financial industry communications since 1979 and has an extensive background in investment and money-management philosophies and strategies. She is a member of the Business Marketing Association and holds the APR accreditation from the Public Relations Society of America. Her work has received numerous awards, including the American Marketing Association’s Gold Peak award. activemanagersresource.com

Linda Ferentchak is the president of Financial Communications Associates. Ms. Ferentchak has worked in financial industry communications since 1979 and has an extensive background in investment and money-management philosophies and strategies. She is a member of the Business Marketing Association and holds the APR accreditation from the Public Relations Society of America. Her work has received numerous awards, including the American Marketing Association’s Gold Peak award. activemanagersresource.com