Alternative investments: Out of clients’ comfort zone?

Alternative investments: Out of clients’ comfort zone?

There’s more to using alternative investments than analyzing correlations and volatility. For financial advisors and their clients, sizing up perceptions and expectations of this growing investment category is a critical first step.

Once the exclusive province of hedge funds, alternative investments are now proliferating throughout the public mutual fund and ETF landscape. That brings them squarely into the domain of the broader investing public and advisory community.

While the broadening of public investment choices is a positive overall development, it can represent a considerable learning curve for investors and even financial advisors. Most investors have not had much experience with alternatives, which can present a challenge for those with a mindset trained to think only about stocks and bonds.

Institutional investors who have experience with alternative investments through hedge funds have already demonstrated a strong acceptance of alternatives packaged in mutual fund or ETF formats (so-called “liquid alts”). An annual survey of alternatives by Morningstar and Barron’s showed that a sea change began occurring in the use of alternative mutual funds at the beginning of this decade.

For example, their 2010 survey showed that 61% of institutions allocating to long-short equity strategies used hedge funds to manage the strategy. By 2012, that number dropped to 26% and the number of institutions using mutual funds for the same strategy rose to 45%. It appears that once these strategies became available as public funds, many institutions began flipping the switch to mutual funds over hedge funds.

The confluence of forces driving this trend should be no big surprise.

On the demand side, there has been a considerable push for lower management fees by retail and institutional investors alike. As a result, the age-old “2 and 20” pricing scheme at hedge funds has been under severe pressure, and once they lost their virtual monopoly on certain strategies, they also lost their ability to hold on to fee-conscious investors.

At the same time, once alternatives hit the public fund world, they became available to everyone rather than just institutions and accredited investors. That made it open season for alternatives among advisors. With the “competition” they have been facing from passive investing vehicles, advisors have been eager to find new ways to differentiate themselves. And let’s face it—the ability to grab assets back from hedge funds represents a sweet victory for advisors.

Meanwhile, from a supply perspective, the issuers of alternative funds have been only too happy to accommodate the demand. With far lower fees, no cut of profits to the managers, no accreditation required, and no lockup periods, fund-packaged alternatives have concrete advantages over hedge funds. As a result, the number of funds considered to represent “alternatives” has ballooned, thanks also in part to a more alternative-friendly SEC than ever before.

No universal definition of alternative investments

Precise figures on the use of alternatives by retail investors and advisors are difficult to come by since there is no universal definition of what constitutes an alternative investment.

Investopedia simply defines one as “an asset that is not one of the conventional investment types, such as stocks, bonds and cash.” That means investments such as private debt and equity, hedge funds, managed futures, real estate (including real estate investment trusts, or REITs), commodities, and derivatives are acknowledged by almost everyone to be alternatives (and, in fact, all are recognized by the Chartered Alternative Investment Analyst Association—CAIA—as such).

But there are investments that still consist of stocks and bonds, albeit managed in novel ways. Among these are long-short equities, covered option writing, high-yield bonds, and equities or bonds from emerging- or frontier-market countries. In addition, there are investments that most would clearly place in the alternatives bucket, such as collectibles, gold and silver coins, art, and even cryptocurrencies, but these are limited to a somewhat small number of investors and are not considered by CAIA to be suitable as large institutional holdings.

Interestingly, the 2008 financial crisis caused both investors and advisors to seek out new ways to reduce their dependency on long equities, and apparently the same thing is happening again now that the market is at the other end of the valuation extreme. More than a few investment firms and financial luminaries have gone public recently with predictions for mid-single-digit returns in equities over the next 5–10 years—a stance that tends to send lots of investors into exploration mode. However, alternatives are rarely used to replace equities or bonds entirely and are generally used sparingly as a diversification mechanism. If we could rename the category with a more accurate moniker, we might consider them to be “complements” rather than “alternatives.” (It wouldn’t be a bad idea for advisors to position them that way to their clients.)

The overall picture of alternatives usage by advisors and their clients is broadening, but it remains shallow in terms of percentage of investable assets. In a 2017 study by Natixis, it was noted that 62% of investors surveyed said it was essential to invest in alternatives to reduce investment risk and 77% said they are willing to consider investments other than stocks and bonds.

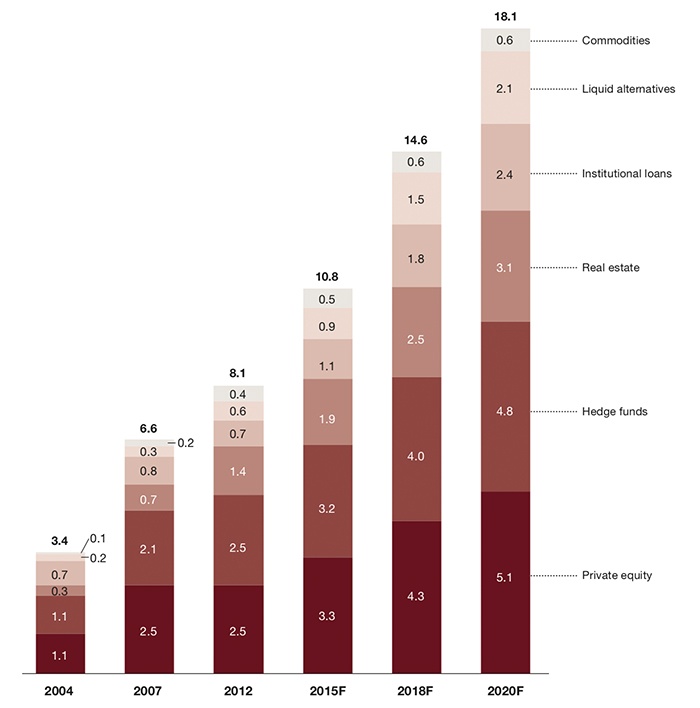

However, in an Investment News article from 2015, Dover Financial Research President Jean Sullivan stated that the average portfolio allocation to alternatives from wire-house advisors hovered then around 5%–10%, indicating that while there is growing interest, advisors are still just tiptoeing into alternatives. That said, with increasing numbers of institutions and financial advisors warming to alternatives, projections from PwC’s Strategy& division show growth in the space of over 20% from 2018 to 2020. Most notably, although still a relatively small piece of the pie, liquid alternatives are projected to grow 40% over the same period.

FIGURE 1: PROJECTED GLOBAL ALTERNATIVE ASSETS BY TYPE

U.S. $ in trillions

Source: PwC Strategy& LLC

Caveats and implications

The study from Natixis also noted, however, that 71% of investors believe alternatives are risky and 63% felt they were “too complicated.” This is where the challenges for advisors begin. Alternatives incorporate a wide assortment of vehicles and strategies plus unique approaches within those strategies. They can range from being essentially just another long equity fund by a different name to a radically different asset, and the variations can have dramatic effects on individual fund performance as well as the performance of an entire portfolio. The sheer array of alternative offerings and the nuances among them is the first big issue for advisors.

In addition, most alternatives funds have relatively brief track records, and most were born in a rising bull market for equities. Advisors will need to do extra homework on fund managers to fully understand the strategy and to determine what to expect from it during other market environments. If financial advisors are going to be introducing alternatives to clients with little or no experience and a high degree of skepticism, they are going to have to be doubly confident in the strategies themselves and capable of explaining them in terms their clients will understand.

Another major issue is that the parameters on which alternatives are measured as investments are often as different from stocks and bonds as night and day. Indeed, the benefits of using alternatives are the advantages they provide in terms of portfolio diversification—advantages that tend to increase with the degree to which the investment differs from stocks and bonds.

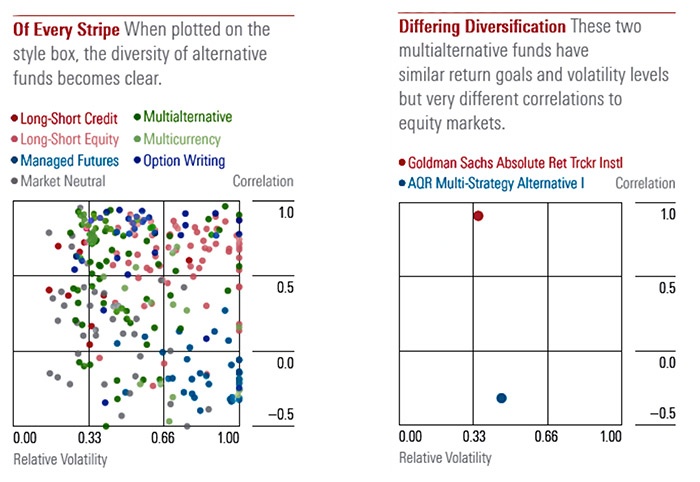

Recognizing that alternatives required a different type of evaluation mechanism than equity funds, Morningstar developed a unique mapping feature just for them. Instead of mapping funds to a grid based on style and capitalization as with equity funds, the alternative mapping feature uses the more “alt-relevant” variables of correlation and volatility. The following examples show how spread out funds can be on these criteria. Viewed in this manner, one can see that many alternatives with similarly descriptive titles might provide very different characteristics to the overall performance of an existing stock and bond portfolio.

FIGURE 2: MAPPING ALTERNATIVES BY RELATIVE VOLATILITY AND EQUITY CORRELATION

Source: Morningstar Direct. Data as of 07/31/2017

Lastly, from an investment management perspective, there are reliable analytical techniques for optimizing portfolios consisting of stocks, bonds, cash, and alternatives. Unfortunately, there is no such playbook for introducing alternatives to your clients. It’s not always going to be about the investment merit or even its diversification properties. It may depend largely on the perceptions and expectations of your clients.

From a behavioral perspective, here are some things financial advisors can anticipate from their clients as they introduce them to the idea of alternatives in their portfolios:

- Perception and representativeness. Since alternative investments represent a vaguely defined category consisting of a kitchen sink full of diverse investments and strategies, perceptions will run the gamut. Clients may not be able to distinguish between an option income fund that represents a minor departure from a broad-based equity fund and a leveraged option volatility trading fund that would represent a different beast entirely. Client perceptions will be based on what is familiar to them or representations they think apply. For example, many people may perceive that long-short equity funds represent a flexible strategy that will be long during bullish periods and short during bearish periods. (If it were only that easy, right?). But that is not the case at all. Long-short equity funds are typically designed around a “130-30” rule that holds 130% in long equities with another 30% short in all market environments. Such funds are going to be 100% net long and thus very highly correlated with the performance of standard long equity funds, even in bear markets.

- Conservative bias. Also called “status quo bias,” this bias describes the complacency that investors fall into, and such bias is common following a 10-year bull market. Simply said, the addition of alternatives will prompt a “why change what works” attitude in many clients (not to mention a hesitation to sell equities that might represent substantial capital gains exposure in taxable accounts). Investors who have decades of experience with long-only stocks and bonds feel they know what to expect from them. For many clients, the natural tendency to stay put may be strong, especially if they don’t feel they fully understand alternatives.

- Framing. How you position the idea of adding alternatives to a client’s portfolio will not only affect whether they accept the suggestion but how they react to it later. It might be wise to avoid the whole idea of labeling these new investments as “alternatives,” which can represent a catchall for things that are often unconventional or untested. People have already indicated that they associate “alternative” with increased risk and complications, so why use a term that is known to have such negative connotations? Using terms such as “diversification” and “complements” may yield more positive reactions because they communicate the concept of risk management rather than more risk.

- Hindsight bias. Adding alternatives to a portfolio is going to subject advisors to after-the-fact blame if it does not work out, and this is difficult to avoid. Clients may understand the concept of diversification in stocks or bonds, but not necessarily with asset classes. They will tend to focus on what the new asset class does, regardless of its effect on the portfolio. They won’t notice the lower volatility overall. What they will notice instead is that either equities continued to do well while the alternative fund languished, or that equities sold off and there was not an attendant rise in the alternative. The way to counter this is through management of client expectations right from the start—and then a candid review once a reasonably long period of results can be analyzed in the context of the total portfolio. It is also essential to position the benefits of alternatives’ diversification as occurring throughout full market cycles, bull and bear markets alike.

- Uncertainty bias. Alternatives that venture into the complex world of structured finance or managed futures are going to be met with an even more skeptical response from clients, and with good reason. They can often be so complex that a client (or even an advisor) might have no idea what to expect from them in terms of performance. Advisors should be particularly cautious about funds for which they and their clients cannot formulate some degree of expectation. It is not going to be advantageous to say “historically this fund has great diversification qualities against equities” when you really have little idea of what it will do in the short term.

- Anchoring. When dealing with anything new, people tend to establish a subliminal reference point from which they can evaluate the new item. For most people, stocks and bonds are what they know, so the natural tendency will be to use one or both as their anchor. Advisors should be prepared to discuss alternatives in that context. For alternatives that are nothing like bonds or stocks, advisors should think specifically about what to use as a reference when explaining them. Otherwise, many clients will revert to comparing an apple with an orange, and that’s where difficulties will arise.

One last thing that investors will have difficulty with is the concept of volatility. Most have problems with the volatility of stock portfolios alone, much less something like futures, distressed debt, or private equity. Clients often don’t realize that the actual historical volatility in equities is greater than what most of them are comfortable losing in any given year—until they experience it for themselves. If they are expecting a return of around 5%–10% annually, a drawdown of that much or more in a single asset class over a few weeks or months is likely to set off alarm bells, even when that is well within historical norms.

Advisors would do well to think carefully about how they want to introduce alternative investments to their clients. Clients need to understand the parameters for any new investment choice in terms of historical volatility, performance in different market regimes, and what diversification benefits they might add to the client’s portfolio. They also need to be educated as to liquidity parameters, which can be quite different for something like a private equity investment than a highly liquid ETF.

If the financial advisor already has a relationship with a trusted third-party investment manager, they may be a valuable resource for help in positioning alternative investments to clients and providing historical data for alternative asset classes. Each client’s personality and investment objectives must be assessed carefully, including their attitudes around risk and their willingness to consider new investment approaches.

The Investment News article mentioned previously quoted Bradley Alford, chief investment officer at Alpha Capital Management, who observed regarding alternatives, “It looks like education around alternatives is starting to pay off. The smart money has been doing it, and now retail has some real access points that they should be taking advantage of.”

Alternatives have great potential as new sources for returns and ways to address portfolio risk management and diversification. But advisors need to understand that alternatives may initially be out of their clients’ comfort zone, requiring a strong commitment to client education and awareness of potential behavioral roadblocks.

The opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of Proactive Advisor Magazine. These opinions are presented for educational purposes only.

Richard Lehman is the founder/CEO of Alt Investing 2.0 and an adjunct finance professor at both UC Berkeley Extension and UCLA Extension. He specializes in behavioral finance and alternative investments, and has authored three books. He has more than 30 years of experience in financial services, working for major Wall Street firms, banks, and financial-data companies.

Richard Lehman is the founder/CEO of Alt Investing 2.0 and an adjunct finance professor at both UC Berkeley Extension and UCLA Extension. He specializes in behavioral finance and alternative investments, and has authored three books. He has more than 30 years of experience in financial services, working for major Wall Street firms, banks, and financial-data companies.

Recent Posts: